The final school bell rings. Children burst through the gates with boundless energy. Rather than spending those precious afternoon hours in front of screens, many Australian families are discovering something valuable. Kids after school activities engage young minds and bodies in ways the classroom simply can’t. These experiences offer far more than simple childcare solutions. They shape character, build skills, and create lasting memories.

Building Social Connections

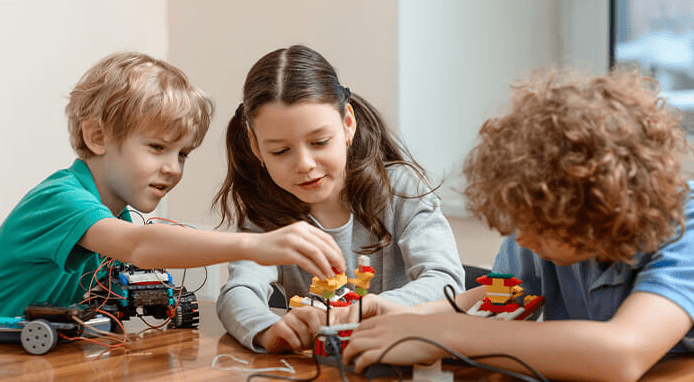

Here’s something most parents miss. The friendships kids form in kids after school activities are fundamentally different from school friendships. There’s no forced proximity or assigned seating. Children gravitate towards others who genuinely share their passions. Whether that’s building robots or perfecting a backflip doesn’t matter.

A shy child who struggles in the classroom might become the most talkative member of a drama group. These settings strip away the social hierarchies that plague school playgrounds. The goalkeeper doesn’t care if you’re the kid who reads alone at lunch. They only care whether you’ll pass the ball. That’s powerful stuff.

Unexpected Skill Transfer

A child learning pottery isn’t just making bowls. They’re developing fine motor control that improves their handwriting. The kid at basketball practice is learning spatial reasoning. That same reasoning helps with geometry later on. Music students develop pattern recognition. Years down the track, that makes coding easier.

The brain doesn’t compartmentalise learning the way we imagine it does. A drama student who learns to project their voice suddenly stops mumbling when ordering at cafés. The violinist who practises scales daily stops complaining about boring homework. They’ve already internalised what sustained effort looks like.

Physical Health Benefits

Forget the obvious stuff about burning energy. The real value is that kids after school activities create what psychologists call “movement memories.” A child who spends years doing gymnastics develops body awareness that prevents injuries decades later. They know how to fall properly. They understand how to gauge distances. Their body moves through space with confidence.

Dancers develop posture that saves them from back problems in middle age. Team sport players learn to read body language instinctively. That skill proves surprisingly useful in job interviews and business meetings down the track.

The Failure Advantage

Schools have become so focused on achievement that many kids reach adolescence never having properly failed at anything. Afternoon programmes provide low-stakes environments where failure isn’t catastrophic. Missing the winning shot hurts. But there’s another game next week. Forgetting your lines during rehearsal is embarrassing. It teaches you to prepare better though.

These small failures inoculate children against the paralysing fear of imperfection that cripples so many adults. The child who learns early that failure is survivable becomes the teenager who tries out for the school musical. Eventually they become the adult who starts their own business.

Emotional Regulation Practice

Watch a child who’s just lost a close match trying to shake hands with the opposing team. That moment teaches emotional control that no classroom lesson can touch. They’re learning to override their immediate feelings. They’re behaving according to values rather than emotions.

The same happens when a child must continue rehearsing despite frustration. Or when they push through the last lap when their body screams to stop. These aren’t just “character building” in some vague sense. They’re literally rewiring neural pathways. The prefrontal cortex strengthens its control over the emotional limbic system.

The Mentorship Gap

Australian families are smaller and more geographically scattered than ever. Many children grow up without regular contact with extended family members who might once have taught them skills or offered guidance. Afternoon programme instructors often fill this gap. They become informal mentors who notice things parents miss.

The swimming coach spots anxiety before it becomes serious. The art teacher recognises giftedness that standardised tests can’t measure. These relationships matter more than we typically acknowledge.

Social Calibration

Children need to learn where they sit in various hierarchies. Not in a cruel way, but realistically. The student who’s top of their class academically might discover they’re decidedly average at chess. The child who struggles with reading might turn out to be an exceptional goalkeeper.

This calibration is healthy. It teaches humility without shame and builds confidence without arrogance. Kids learn that everyone’s brilliant at something and hopeless at other things. That’s possibly the most important lesson for navigating adult life.

Conclusion

The real value of kids after school activities lies in what we don’t immediately see. Yes, children gain skills and fitness and friendships. But more importantly, they’re building neural architecture for resilience. They’re collecting identity anchors and practising failure recovery. They’re forming mentorship relationships outside their immediate family. They’re learning that effort compounds and that temporary discomfort produces lasting capability. Who they are isn’t limited to who they are at school. These aren’t just nice additions to childhood. They’re essential infrastructure for becoming a functional adult.